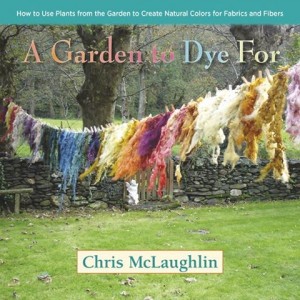

A Garden to Dye For by Chris McLaughlin is a natural dye book designed for gardeners, and natural dyers who may have not connected their garden endeavours with the dye pot (yet). From edible dye gardens, to rose and flower dye gardens there is an option for every gardener, natural dyer, and space constraint.

Overview:

The book includes dye recipes, but explains them through rule-of-thumb rather than exact measurements. Only have a few pounds of wool and a bit of a particular dye plant? Go ahead and experiment, that’s the whole fun of natural dyes.

If you’ve wondered why you didn’t get the colour you were expecting, there are even some tips and explanations of how “accidental” modifiers could impact your dye efforts. I for one had never realized that black beans were an anthocyanin dye and would give pink in an alkaline environment and blue in an acidic environment (same as purple cabbage).

If you’ve heard a dye is fugitive it doesn’t mean you can’t use it. Chris suggests some creative uses for known fugitive dyes, such as red cabbage or beets. Uses such as play-dough, or Easter eggs where colour fastness is not an issue.

What I liked:

Throughout Chris’s book there is an element of cheerful experimentation. The colour is there, it is just a matter of experimenting until successful. If one likes the colour achieved from one plant, with one fibre, why not try it with other fibres, mordents, or modifiers to see how it changes? Some dyes maybe fugitive, others have increased fastness, but they are all fun to play and experiment with. After all, not every colour needs to last forever and some natural colours seem to increase in complexity and beauty while they fade, onion skins are an example.

The “recipes” were more like guidelines and seemed to permit and encourage experimentation. I have read several dye books where the recipes had to be exact to the microgram, according to the author, or it would not be successful. Chris’s approach is refreshing in that it does not have the negative view on approximation that is often expressed. There was also a positive light on the range of hues possible from plants, and the cheerful perspective of experimenting until the desired shade was achieved. I have encountered books and individuals who said that “this shade can be gotten, but you won’t get it so don’t try” which is often enough to make me go and try just to prove them wrong, but that attitude loses the joy of the experiment since I certainly don’t want to prove them right!

A few other comments:

There was a slight mention of dying with “invasive species” and it would have been nice to go a bit more in-depth on that option. Invasive species are one class of plants where harvesting should not be sustainable, but rather with the goal of eradication. The picture for that section was of the Woad plant, classed as an invasive species in California where Chris is from, but other areas may not have the same classification. Even in California woad would be a viable source of blue, it just has to be wild-eradicated rather than grown in a garden (more garden weeds?). On the bright side, it did give me some ideas on how to deal with some of my local invasive species, more dye vats anyone?

Conclusion:

If you are interested in a gardening and natural dyeing book that is different from the norm look no further. A Garden to Dye For is a gardening book with the excuse of natural dyeing and the spirit of exploration, experimentation, and adventure. No more will you be told to measure your dye-vat gram by gram, or have the exact ratio of fibre to dye material. Instead, you will be given guidelines and released to explore and try it on your own.

From explanations on what variables might impact the colour, to how to adjust and compensate for unexpected colours, there is a wealth of information in this engaging and fascinating book.

I received a free review copy of this book in exchange for an honest review.

Pictures used with permission of Chris McLaughlin and St Lynn’s Press.